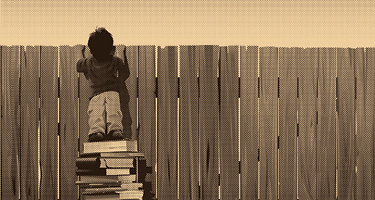

If you spend any time with children, you know that they’re both adept at and perfectly comfortable asking basic questions: Why is the sky blue? Why do I have to go to bed? When thinking about assessing, managing and resolving disputes, we older folks can benefit as well from asking more “why” questions rather than assuming that whatever is before us has been well thought out.

I’ve been able to test this strategy in three general counsel roles, each with similar results and benefits. Allow me to explain.

With no prior in-house experience, I was hired as general counsel by a previous client—a Fortune 1000 company without in-house attorneys. After I cautioned the CEO that I didn’t really know what general counsel do, he replied simply, “You’ll figure it out.” That feedback emboldened me—I took it as permission to go back to basics, or what I like to call practicing curiosity.

As you might suspect, a new GC typically inherits an array of active and threatened disputes, some bigger and more disruptive than others. Stepping into my first GC position and two that followed, I kept my process the same: Review each matter bigger than the proverbial breadbox in order to assess whether the company was on the best path.

Interestingly, the results of that review were nearly identical at all three. Most of the time our legal position appeared strong (the “good” disputes); some were less clear about the merits of the course we were on (the “ambiguous” disputes); and some appeared to make little sense when I measured our prospects of winning and the anticipated costs of getting there (the “bad” disputes).

Less clear across all three categories was why we were actively litigating rather than trying to solve the matter promptly via direct negotiation or mediation. We therefore instituted the rule of practicing curiosity, both internally and externally.

Thus: If our legal position appeared good, why not show the other side our best case right away to prompt a compromise reflecting that reality? Likewise, even if we were confident about our position, why not learn from our counterpart if we had missed something important? (It does happen from time to time.)

If our position was ambiguous, meanwhile, why not talk directly to the other side to better understand what they saw differently? If they had information to support their contrary view, wouldn’t we be better off knowing that sooner rather than later? Conversely, if they miscalculated, wouldn’t we want to show them our best case immediately, before direct and sunk costs grow all around?

Finally, if the dispute appeared bad for us from the outset, why would we think it might improve, rather than metastasize, over time? How would kicking the can down the road produce a better net result for us, factoring in direct legal expenses and indirect costs related to people and overall disruption?

All these categories warrant engaging early and often with opposing counsel, practicing genuine curiosity as well as sharing information. Think of it as show and tell: You can’t be fully effective without doing both. In every instance, doing so dramatically reduced the average direct and indirect costs and time required to resolve most disputes, compared to earlier periods when the company followed the same old, same old litigation path.

Importantly, practicing curiosity does not mean immediately defaulting to mediation. While an experienced mediator can facilitate an exchange of information and in turn help settle the dispute, direct exchanges between adversaries may suffice to strike a deal.

As we learned, some disputes still require a third-party neutral. However, prior and direct dialogue between the two sides helps everyone prepare for mediation. Especially when other constituents or decision makers are involved—senior executives, insurers, family members—pre-mediation discussions enable everyone to realistically handicap a dispute’s upsides and downsides, improving the prospects of a mediated outcome.

Why don’t people do this all the time, then? Here are a few common rationales, along with my rebuttal.

For strategic reasons, we can’t detail our claims and defenses early on. Yes, situations exist in which one side doesn’t want to disclose its position until after a key deposition or two. But such scenarios are rare in the real world. Typically, skilled counsel and clients anticipate arguments and alleged facts, so direct dialogue can proceed at the outset.

For reasons of precedent or principle, we can’t talk settlement. In truth, most situations are unique, and no real precedent is at stake. As well, a purported precedent might turn out to be a bad one, depending on how the current litigation ends.

The argument about principle is similarly overused, predicated on the notion that a win here will deter other, similar claims. No data exists to support that premise—I know this, having asked for it over decades in the mediator’s chair. Equally important, competent counsel generally won’t be deterred from pursuing a meritorious claim no matter how an earlier case ended.

The other side won’t listen to reason. It is true that experienced counsel sometimes discourage early settlement talks because the counterparty has been unreasonable or obstreperous, citing examples of satellite disputes or uncivil behavior. But in my experience, we decided to plow forward anyway, usually with positive outcomes.

Aided by a mediator skilled in managing the room as well as the case assessment, the putative bad behavior rarely emerged. Indeed, skilled counsel are usually skilled in valuing disputes. When one is armed with key facts and a neutral’s perspective, the dispute usually heads toward the appropriate valuation. Time saved, money saved—and sometimes people saved as well.

The trend away from early, substantive dialogue between adversaries has been costly in all these terms. But it can be reversed. Channel your inner child. Ask the most basic “why” questions—of your folks and the other side alike—from the outset, and keep asking them. Show and tell works.