Now more than ever, practicing law is a team sport. Clients expect smooth, effective coordination across practice areas, seniority levels, dispersed offices and different firms—even in stressful circumstances with tight deadlines and high stakes. A “servant leadership” culture is essential to promoting the sense of empowerment, appreciation and support that yields peak performance.

The term “servant leader” might sound soft. Yet it’s at the heart of Navy SEAL culture, with the head of a group assuming “extreme ownership” of every team member’s actions, including mistakes and failures. The animating mantra is “no bad teams, only bad leaders,” which pretty much eliminates finger pointing or excuse making at the top.

In the corporate world, a servant leadership ethic has been embraced by large, operationally complex companies such as Delta Air Lines to shape their business around the globe. Delta CEO Ed Bastian describes its culture as a “virtuous circle” of putting people first, which means taking care of employees so they take care of customers, who give Delta loyalty, which pays off for ownership, which then invests more in the company. In short, servant leadership as he describes it creates wins for everyone it touches.

Large law firms looking to use this leadership model face a few challenges.

- It’s not how we’ve been trained. Unlike in an MBA program, team projects that teach collaborative skills are not a staple of law school curricula.

- Once hired, an associate knows that opportunities for partnership are finite, which can work against a spirit of collaboration.

- As a lawyer advances, the metrics that determine compensation can cause competition over who gets credit.

While these aspects of law firm life might suggest otherwise, my experience is that servant leadership can be effective in a large firm. In fact, I see it as necessary to deliver on client expectations. A memory from my associate years illustrates the point.

Our practice group was joined by a capable associate hired from a West Coast firm, and he and I often worked together. He became a good friend, and we made partner at the same time. Later, after he went in-house, he became an excellent client. As time passed, he told me that early on, he was surprised that I had befriended and was helpful to him given that we were in the same associate class in the same practice area. For my part, I never regarded him as a rival but rather as an extremely bright and thoughtful colleague as well as a genuinely good person. Instead of competing, I reasoned we could help each other succeed, and we did.

How do we encourage such thinking in today’s environment? First, the firm should work to select team players and encourage team play from day one. Admittedly, this is not always easy and must be done with care, but in the end it’s worth it.

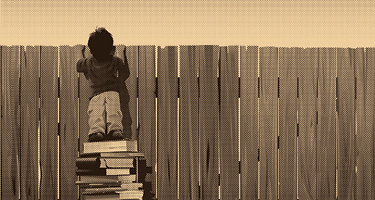

Second, every associate deserves to be mentored and to feel supported and empowered in his or her aspirations. Partners must resist the ever-present instinct to micromanage work while at the same time providing coaching and real-time feedback. The goal should be to get everyone who comes to work at the firm to a better place as a result of being there.

Next, partners should be open to learning from and, in some instances, being mentored by less senior lawyers. As John Wooden once said, “It is what you learn after you know it all that counts.”

Also, everyone’s work life and personal life can be bumpy at times. A kind word and empathy, particularly during a difficult stretch, will go a long way.

Finally, when planning the future of their firm, partners and others should pointedly work to identify promising young leaders and encourage their development. This entails establishing an experience track of team leader, practice group leader and other roles that expose rising lawyers to the challenges of organizational and personnel management. Also, leadership development is a specialized discipline—be sure to engage with outside experts who can offer sound insights.

Practicing law is and always will be a people business, no matter how large a firm grows. Following the principles of servant leadership, the law firm that creates a virtuous cycle by putting its people first so they can most optimally serve their clients will ultimately be the most successful—and will attract and retain the best talent.